William Shakespeare (1564–1616) was barely literate, but he could not have died more poetically: on the same day and month he was born, April 23. Today would have been his 461st birthday (if people lived for centuries), as we commemorate the 409th anniversary of his death.

I’m not ready to lay out a case for who wrote the works attributed to William Shakespeare, because I don’t think the world is ready to entertain the idea that the individual widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language (according to Wikipedia, anyway) was a woman—let alone one who grew up on a farm, in a rigidly patriarchal society that didn’t educate girls.

This is a woman whom scholars claim to know very little about, outside public records. They dismiss her as a footnote in the life of a literary genius—not realizing it was she who wrote the plays and poems they study, teach, and publish criticism on.

No, the time just doesn’t feel right—though perhaps it is ripe. We probably need this information now, if only to expand our thinking a bit—to encompass the fact that the configuration of sex organs within the human body has no bearing on the soul’s depth to feel or on the mind’s capacity to learn, imagine, or create. Ultimately, the sex of the person who wrote Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream shouldn’t matter—which, perhaps, is all the meaning in answering the authorship question once and for all.

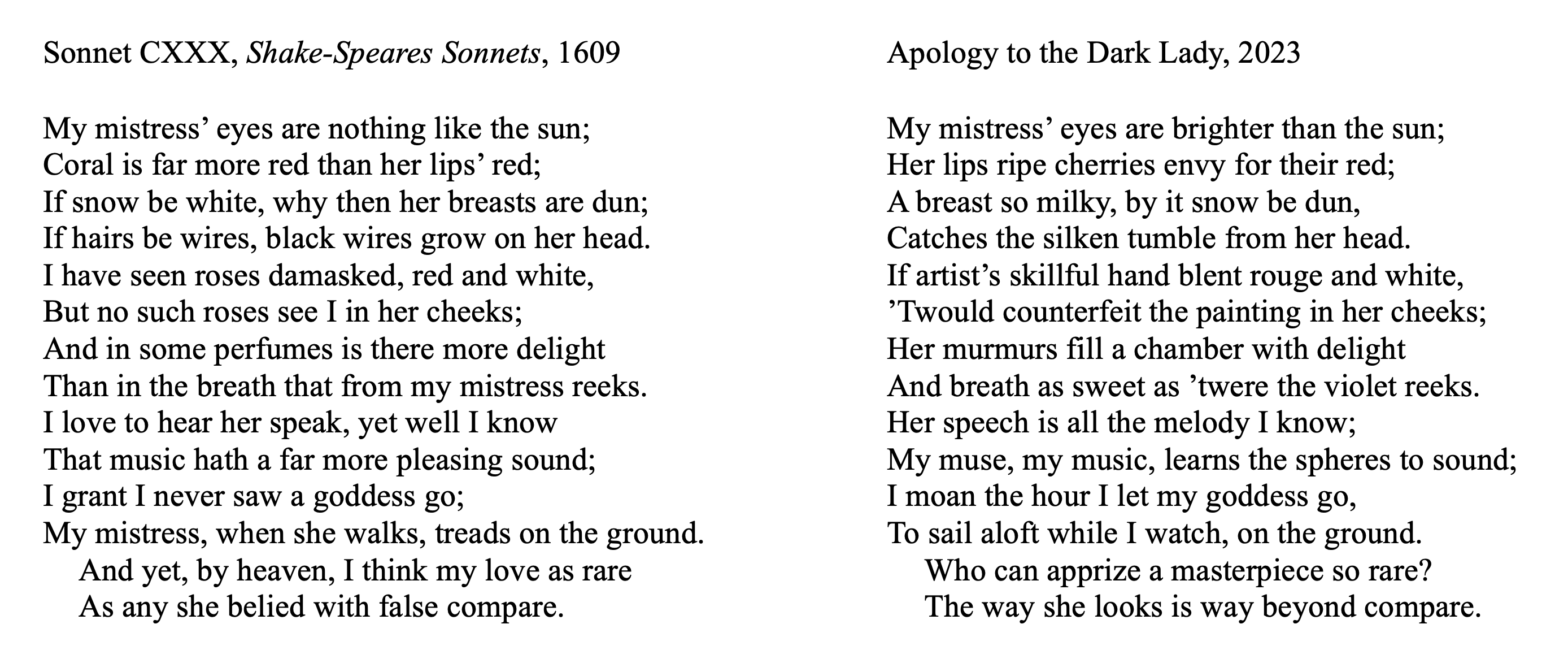

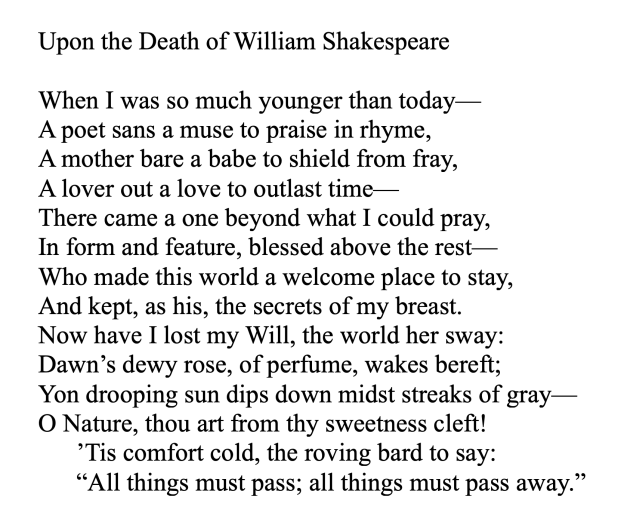

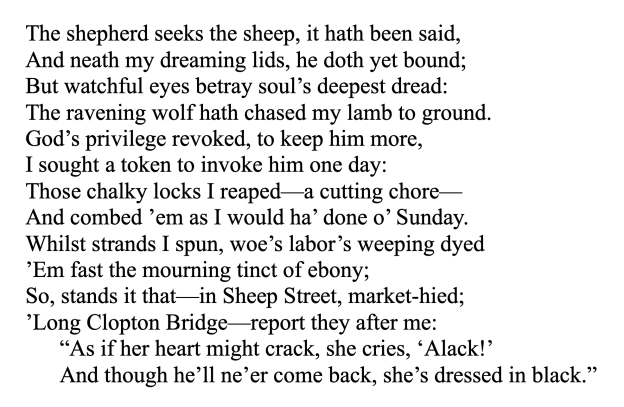

Today, I am sharing a sonnet that might have been penned by Anne Hathaway, William Shakespeare’s wife of thirty-three years, upon the death of her husband. It follows the sonnet form that was popularized, though not invented, by the writer of Shakespeare’s works—but I have leveled up the difficulty a bit. (I’m a bookish kind of daredevil.) Here’s the rhyme scheme of the traditional Shakespearean sonnet:

ABAB CDCD EFEF GG

The different letters represent pairs of lines that rhyme with each other: so, the first and third (A an A), the second and fourth (B and B), the fifth and seventh (C and C)—all the way to the closing couplet (G and G). Today’s sonnet, however, uses the following, somewhat more ambitious rhyming pattern:

ABAB ACAC ADAD AA

What this means is that over half the lines in the poem (eight out of fourteen) rhyme with each other: specifically, lines 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 14. This more demanding rhyme scheme, which requires additional craft from the poet, pays homage to the profound specialness of the subject.

From Anne Hathaway…

Each sonnet in my series concludes with lyrics written by the original Paul McCartney (who died in 1966). I took the last line of today’s sonnet from the title track of George Harrison’s triple album All Things Must Pass (1970). I suspect Paul was inspired to write “All Things Must Pass” (the song) by his mother’s passing, when he was fourteen; or by the death of the Beatles’ first bassist, Stuart Sutcliffe, when Paul was nineteen. The song offers words of comfort from the deceased, using natural phenomena (sunrise, sunset, a cloudburst) as metaphors.

In previous posts, I have noted Paul McCartney’s systematic use of meter in his lyrics. In fact, Paul employs enough of the metrical “feet” (rhythmic units) required for Shakespearean sonnets that I have gleaned about two hundred possible last lines for sonnets so far. (Fans might also notice that today’s sonnet opens with a nod to the Beatles’ 1965 classic “Help!”)

It should probably come as no surprise that English student Paul McCartney wrote at least one Shakespearean-style sonnet. This poem has survived, mostly intact. Paul’s replacement published it in his memoir, as his own—but modified two lines to refer to his wife Linda, who died in 1998. While I do not wish to diminish the sentiment of those lines by omitting them below, they are not Paul’s. And Paul would have been mortified to take credit for words he did not write (especially when they contained a punctuation error and a questionable rhyming choice). So, here is the greater part of a Shakespearean sonnet written by young Paul McCartney following the death of his mother:

She was the source of all that life could bring.

Each day her glory woke the morning rays.

Her voice was first of all the birds to sing.

It was her calling to ignite the days.

…

…

An advocate for every beating heart,

She would defend each child and each mouse.

But now her face and song are not as clear.

Her image and her voice are in a haze.

Though still she whispers guidance in my ear,

Don’t see her ’round the house as much these days.

The more delight we find in love and song,

The more we’re left to miss them when they’re gone.

Regarding the subject matter of the two missing lines, I can only speculate. Perhaps they refer to Mary McCartney’s work as a midwife and as the head nurse of a hospital maternity ward—hence the words “advocate,” “beating heart,” “defend,” and “child” in the two remaining lines of the quatrain.

In closing, I can attest that a sonnet, like a song, makes a pretty little container to put one’s grief in.

This time last week (as I write), I was enjoying afternoon tea at The Berkeley, a lovely hotel in the Knightsbridge area of London. To be more precise, given the time difference between England’s capital and where I am now, afternoon tea was a recent pleasant memory.

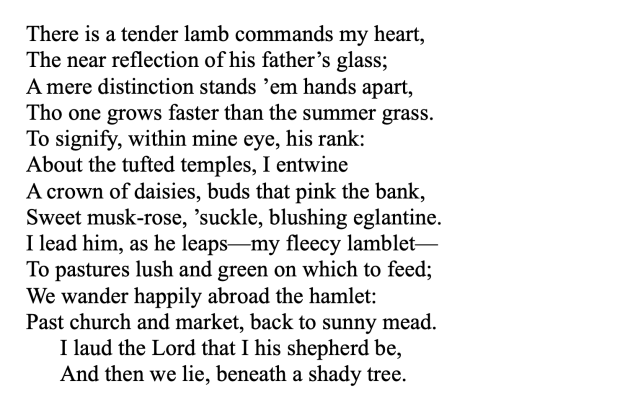

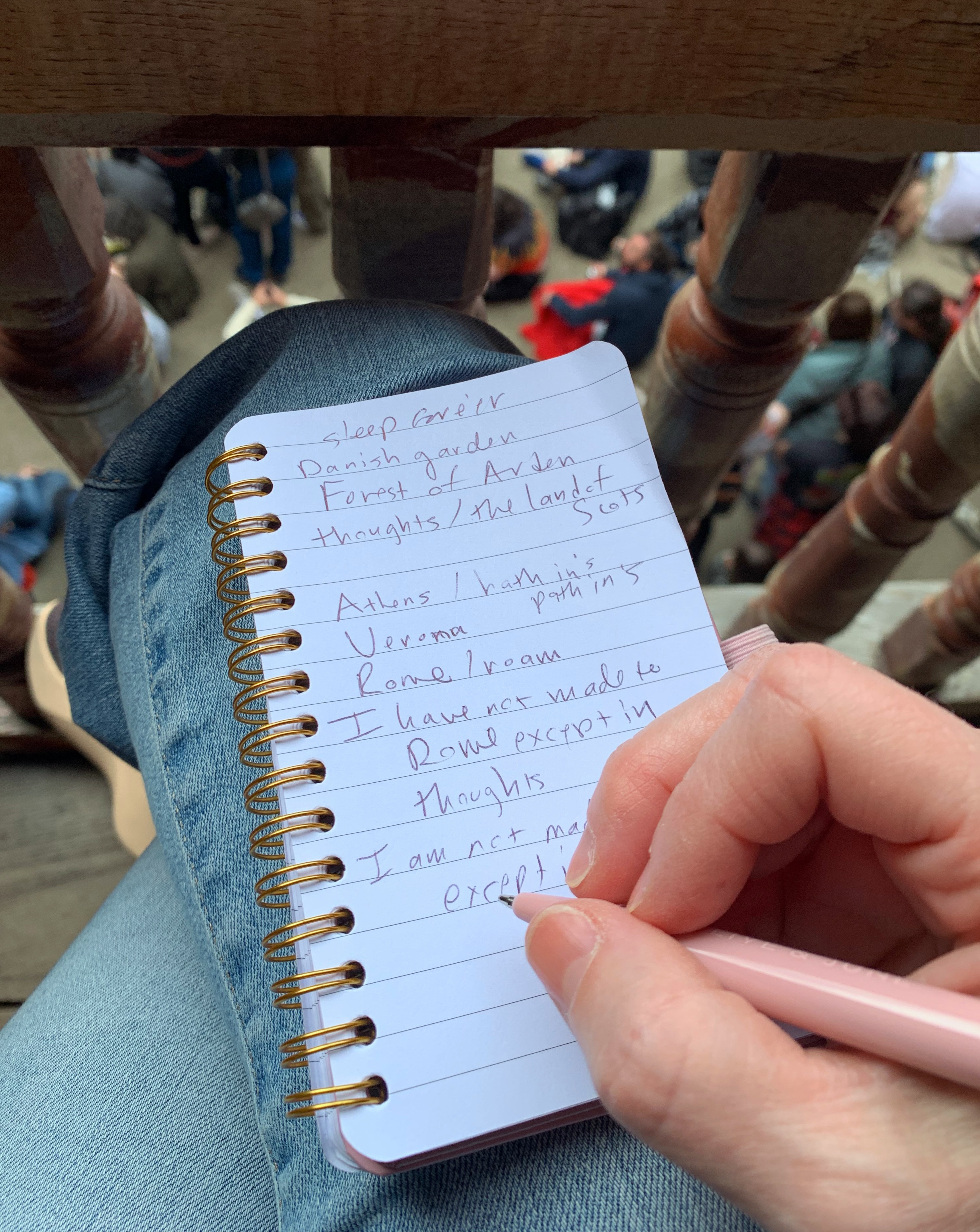

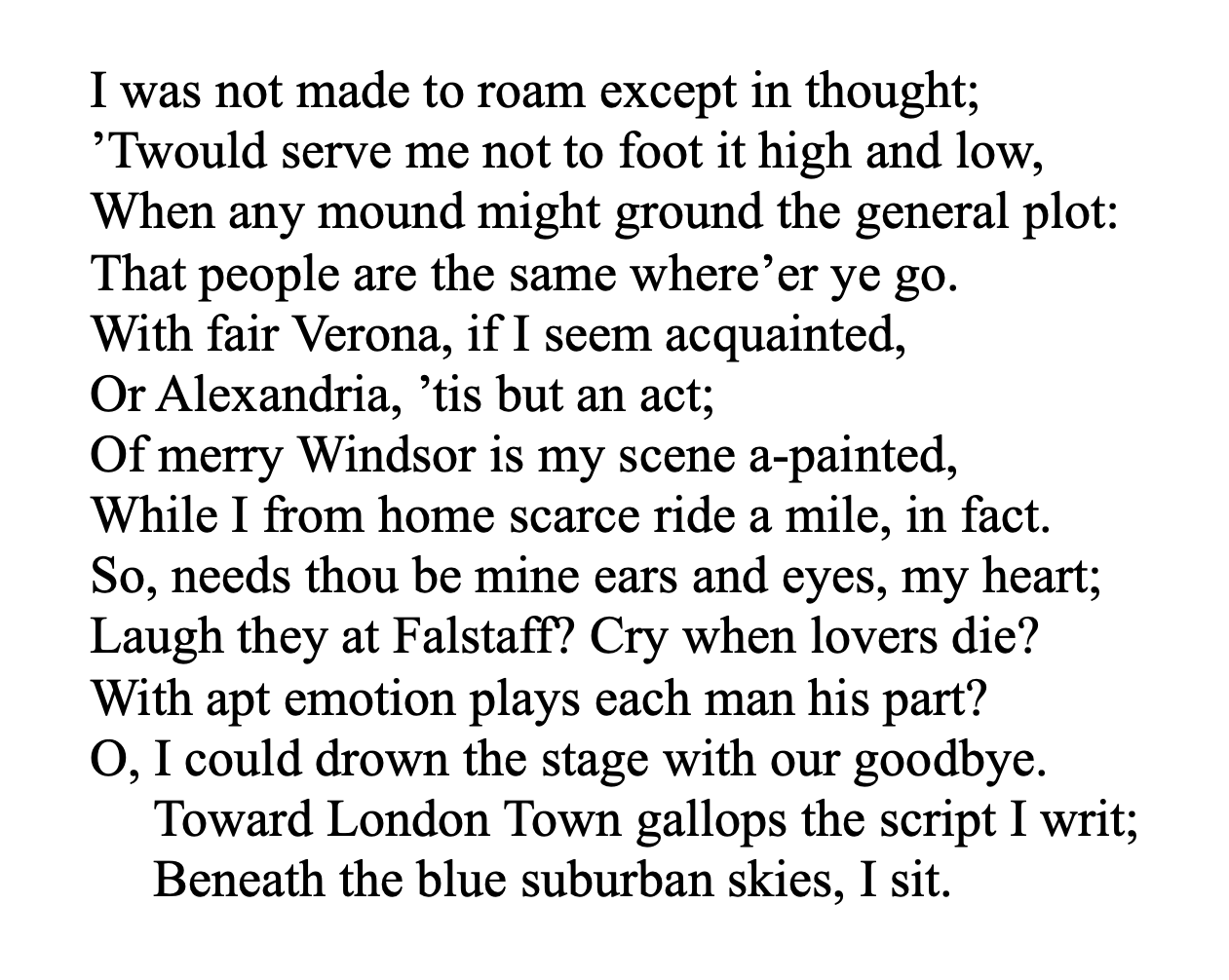

This time last week (as I write), I was enjoying afternoon tea at The Berkeley, a lovely hotel in the Knightsbridge area of London. To be more precise, given the time difference between England’s capital and where I am now, afternoon tea was a recent pleasant memory. Earlier in the week, I had attended two performances at Shakespeare’s Globe, located on the south bank of the River Thames—so perhaps it’s not a surprise that I have a new sonnet to share with you! I jotted down some ideas for the sonnet during the interval (British for “intermission”) in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, on Tuesday. By The Comedy of Errors, on Thursday, the poem was starting to take shape.

Earlier in the week, I had attended two performances at Shakespeare’s Globe, located on the south bank of the River Thames—so perhaps it’s not a surprise that I have a new sonnet to share with you! I jotted down some ideas for the sonnet during the interval (British for “intermission”) in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, on Tuesday. By The Comedy of Errors, on Thursday, the poem was starting to take shape.

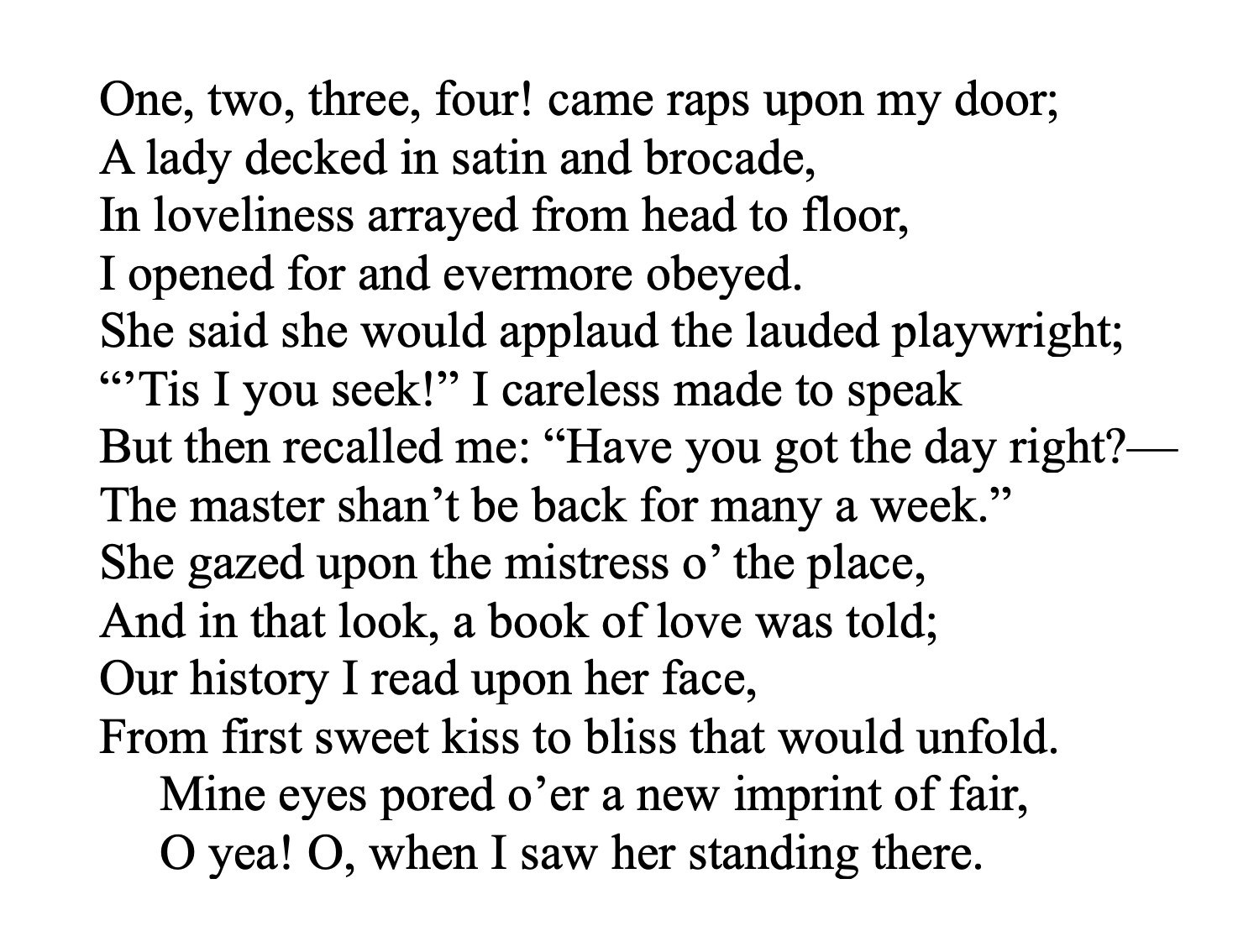

The poem I am sharing today strongly suggests the identity of the person who wrote the works attributed to William Shakespeare. That’s right: the pesky “authorship question” has finally been solved!

The poem I am sharing today strongly suggests the identity of the person who wrote the works attributed to William Shakespeare. That’s right: the pesky “authorship question” has finally been solved!