In my last post, I said that in my next post, I would tell you how the original Paul McCartney broke his left front tooth—which is to say, who broke it for him. But now is not the time for that story.

People remember where they were when they heard John Lennon had been shot and killed—a shocking event that took place forty-four years ago today, on the evening of Monday, December 8, 1980. Many Americans found out while watching Monday Night Football. As the game was winding down, the commentators in the booth—Howard Cosell, Frank Gifford, and Don Meredith—received word of Lennon’s death.

Cosell had interviewed Lennon several times and been friendly with him. The legendary sports broadcaster questioned the appropriateness of disclosing, against the backdrop of an athletic contest, the music icon’s passing. But during a timeout, with three seconds left in regulation, and prompted by Gifford, Cosell made the following announcement:

Remember, this is just a football game, no matter who wins or loses. An unspeakable tragedy, confirmed to us by ABC News in New York City: John Lennon, outside of his apartment building on the West Side of New York City—the most famous, perhaps, of all of the Beatles—shot twice in the back, rushed to Roosevelt Hospital. Dead on arrival.

Cosell then offered a poignant segue: “Hard to go back to the game after that news flash.” The Miami Dolphins would win in overtime, beating the New England Patriots 16 to 13.

As for me, I have a precise recollection of where I was when I learned John Lennon had died—or do I?

Where Was I When I Heard?

When John Lennon was a forty-year-old former Beatle living in Manhattan, I was a twelve-year-old girl living in Encino, a suburb of Los Angeles. On the morning after Lennon’s murder, I found myself in Miss Brown’s classroom. Ellen Brown, my fifth-grade teacher, had short, wavy hair. She was in her twenties, from my best guess now. I remember her as petite, close in stature to some of her students. I admired many of my teachers growing up; Miss Brown, especially, fostered my creativity. She continues to hold a very special place in my heart.

That Tuesday morning, Miss Brown picked up a newspaper from her desk. She blurted out, “John Lennon died last night!” She was shaken. A frantic energy filled the room—where I didn’t seem quite to belong, like I was just floating through. When Miss Brown uttered John Lennon’s name, I recognized it as that of a rock musician. At the time, I was unsure about rock music. My parents listened to the Carpenters, Barry Manilow, and Johnny Mathis; I had the sense that rock was edgy, dark, and dangerous. Such were my thoughts in the moment I found out John Lennon had died.

But there’s a problem with the scenario I just described: It couldn’t possibly have occurred within the rules generally accepted as governing the material world. You see, in December 1980, I was in the seventh grade, not the fifth; and I was enrolled at a different school. I hadn’t been one of Miss Brown’s pupils since June 1979. Yet I can still register the shock and distress in her voice as she announced John Lennon had died. I know I’m recalling something that actually happened; at the same time, the memory must be false.

When I heard (again) about John Lennon’s murder, I had a sense of déjà vu: “Wasn’t he dead already?”

I wonder if Ellen Brown is still teaching. I wonder if she remembers where she was when she found out John Lennon had been slain—and if that location was a small elementary school in the San Fernando Valley, in the room where she taught fifth grade.

Paul’s Posthumous Eulogy at John’s Imaginary Funeral

With John Lennon’s passing, thirty-seven-year-old George Harrison lost his third Beatle brother: Paul McCartney had died fourteen years earlier, in 1966. Stuart Sutcliffe, the fledgling group’s original bassist, had perished four years before that, in 1962. But in the eyes of the world, John Lennon was the first Beatle to “shuffle off this mortal coil.” Had Paul McCartney been alive at the time, and delivered his bandmate’s eulogy, he undoubtedly would have quoted Shakespeare, annoyingly, just like that.

John Lennon didn’t have a funeral. Therefore, he didn’t have a traditional eulogy. Four years ago today, on the fortieth anniversary of John’s death, I felt inspired to write such a commendatory oration—as if spoken by Paul now. Or four years ago. (When you read it, try to maintain a very casual relationship with time.) I didn’t finish it. I barely started it. You might think of it as the first page of Paul McCartney’s eulogy for John Lennon—dropped as Paul left the podium, picked up by an audience member, and now mounted and framed and being auctioned by Sotheby’s with a starting bid of $90,000.

A eulogy probably shouldn’t require footnotes, but to appreciate Paul’s hilarious opening remark, you’ll need the following backstory: John and Paul knew each other before, in the 1800s, in London. They were a married couple—practitioners of the literary arts. Their union was free from neither drama nor heartache. Ringo was their only child, out of four, to survive past the age of three. George was there, too, as a poet and artist who worked with Paul’s mother. All would go on to have Wikipedia articles written about them, as figures of the Romantic Period.

The rest of this section has been taken almost verbatim from my journal entry on December 8, 2020. I have made some minor edits for clarity.

***

So, imagine twenty-four-year-old Paul McCartney (conveniently frozen in time at the age he died) in a black suit and tie with a crisp white shirt, dark hair skimming his brows. He approaches the microphone in an enormous hall: open casket…John Lennon’s beautiful hair…an embarrassment of flowers…friends and lovers, celebrities, celebrity friends and lovers. Paul brings up a guitar and leans it against something. Is he going to play “Yesterday”?

Paul’s eyes are cast down, lips pressed tight, making his cheeks seem round and full. He is clean-shaven, but a five o’clock shadow is already forming—and it’s only 10 a.m. He raises his large hazel eyes to look toward the back, not at anyone in particular. But then he takes a breath, makes eye contact with people around the room. His eyes brighten and his brows rise as he meets the gaze of an individual mourner; his mouth relaxes into a smile qualified by grief. He clears his throat and begins.

John Lennon was the love of my lives. That’s a little reincarnation humour. Nothing? Is this thing on? [tap, tap]

Yesterday, I read an article saying that although John Lennon “could be mean and nasty,” he was an idealistic pacificist because he wrote “Imagine” and “Revolution.”

“No!” I wanted to scream. “I wrote those songs! He STOLE them from me! Paul McCartney is the idealistic pacifist!” I recognize the irony in the vitriol of my response. But is that what a friend does? Claim authorship for your songs? Shortly before his death, John gave Yoko partial credit for writing “Imagine.” I think the guilt was getting to him, and he wanted to share it—to make someone else complicit with him.

The reason John Lennon is an enigma, the reason he appears so self-contradictory, the reason you still won’t understand him forty years from now, is that our legacies have become comingled, his and mine. Hopelessly and irrevocably comingled, I fear, in history and in the common perception. But even when you parse out his contributions from mine, his penchants from mine, his philosophies from mine, enigma remains.

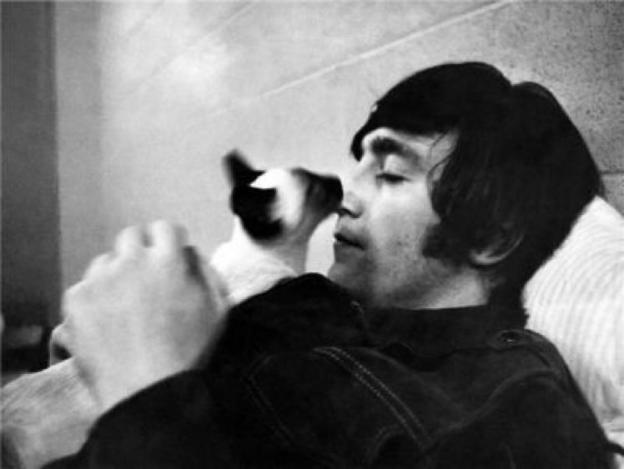

John Lennon was a man who liked cats. Kittens, too, although everyone likes those. After I died, he purchased two kittens and gave them to my replacement, as a sort of housewarming gift. John named the baby felines Pyramus and Thisbe, after the two characters from A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM that he and I portrayed on TV. So, yes, ouch.

Did you know those glasses he made famous didn’t help him see?

I’m not worried about tarnishing John’s memory. He has loyal fans, and they won’t stop loving him. Nor should they. I haven’t.

The Word Is Love

When I found out, as a preteen in Southern California, that John Lennon had been fatally wounded, I had no idea he and I were once Beatles together, making the music of which I was now wary. When John, Paul, George, and Ringo came together in the 1950s and early 1960s, they didn’t realize they had known each other, either personally or peripherally, more than a hundred years earlier. But I’m willing to bet they felt familiar, even like family—at least on a subconscious level. As a sidenote, Paul and George had also been parent and child in Elizabethan England, and spouses in Biblical times.

So, what’s the point of all this coming and going, this leaving and returning, only to meet up again with the same souls—wearing different clothes, doing different jobs, navigating different circumstances, in different parts of the world? Love. Love is not the “official” purpose of reincarnation, which has more to do with karma and the settling of old scores. But it’s the purpose I choose, and the purpose anyone can choose. To feel, and to invite others to feel—love. Love, in its multiple expressions: peace, joy, unity. These may sound like ideals to be realized only fleetingly, if at all—but they are, in truth, the only reality.

Paul appears to have penned at least the verses to “Imagine” in New York City, possibly during the Beatles’ first visit. He would have been twenty-one at the time. When Paul was growing up in Liverpool, America must have seemed a very distant place. But here he was, and the world was suddenly close—and small, really. And filled with people just like the ones at home. Perhaps such thoughts inspired “Imagine,” in which Paul voices a wish for global unity: “Imagine all the people sharing all the world.” He hopes everyone will join him in “a brotherhood of man.” One might interpret such sentiments as idealistic. But I would argue they are perfectly realistic. Only love will save the world. Can you think of anything else that will?

In “Imagine,” Paul acknowledges his own seeming idealism: “You may say I’m a dreamer.” But in the next line (“But I’m not the only one”), he lets us know he is aware of others just like him. And you can choose, at any time, to be among them.

Paul McCartney wrote a lot of songs about love: “She Loves You,” “Love Me Do,” “P.S. I Love You,” “It’s Only Love,” “All My Loving,” “And I Love Her,” “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away,” “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “Love You To,” “A World Without Love,” “Love,” “My Love,” “Oh My Love,” “Real Love,” “Silly Love Songs”—and these are just the ones with “love” in the title. I think we can assume love was very important to Paul, that he thought it was the answer—to probably anything. In “The Word,” Paul identifies love as his way of being, and as the way:

Spread the word and you’ll be free

Spread the word and be like me

Spread the word I’m thinking of

Have you heard the word is love?…Give the word a chance to say

That the word is just the way

It’s the word I’m thinking of

And the only word is love

Perhaps the song that sums up Paul’s philosophy most succinctly is “All You Need Is Love.” It was performed by the Beatles at EMI Studios on June 25, 1967, for a live satellite television production seen by more than 400 million people in 25 countries. Even I am astonished by how much Paul’s replacement resembles him, at times, in this video. But don’t overlook the two “Paul is dead” clues uttered by John toward the end (“Yesterday,” at 3:12; and, “Loved you, yeah, yeah, yeah / We loved you, yeah, yeah, yeah,” at 3:22).

I daresay you’d be on solid ground to decry the cover-up of Paul McCartney’s death and the plunder of his musical archive as morally indefensible. But during the four minutes of the broadcast of “All You Need Is Love,” one in eight people on Earth heard Paul’s simple and heartfelt message. And that means a lot.

CREDIT: The photo at the top of this post shows John Lennon holding a cat backstage at Shea Stadium, in New York City, on August 5, 1965. Photo by Bob Whitaker/Getty Images. Borrowed without permission but with tremendous gratitude. The article referenced in Paul’s eulogy can be found here.