The original Paul McCartney of the Beatles died fifty-eight years ago today, on Sunday, October 9, 1966. He was twenty-four.

I do not have confirmation that Paul McCartney died on this particular day. But October 9, 1966, falls squarely between Paul’s last well-documented appearance (when he was filmed with Ringo at the Melody Maker Awards, in London, on September 13, 1966) and his replacement’s first official appearance as a Beatle (when he was filmed with John, George, and Ringo arriving for a recording session at EMI Studios, also in London, on November 24, 1966).

In recognition of this anniversary of Paul’s passing, I am sharing a new recording—and some information I can’t keep to myself any longer. In I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings (1969), the first volume of Maya Angelou’s autobiography, the poet observes: “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” When this quote found me, a few weeks ago, it resonated deeply. It seemed to grant me permission to tell my tale—if only for my own relief.

Ultimately, however, I want the truth to be out there—for Paul.

I am certain of very few things in this world, but I am 100 percent certain that the original Paul McCartney of the Beatles died and was replaced. If you’re thinking, “This is rubbish,” I don’t blame you. It’s an astonishing claim. But I ask you to keep reading, if only for a good story.

The following account represents a combination of research, observation, interpretation, analysis, reasoning, and intuition. I welcome corrections, from people who were there, to any erroneous conclusions I might have reached. I am hoping to set the record straight—not add to the mountain of false information already out there about the Beatles.

Going Through a Dead Man’s Pockets

I am almost 100 percent certain that many of the songs left behind by the original Paul McCartney (as lyric sheets and home demos) were stolen by the Beatles—resulting in some of their best-known hits. A “songwriting fingerprint” distinguishes Paul’s lyrics. As it turns out, he was very prolific. Paul’s backlog sustained the Beatles for nearly four years after his death and then formed the backbone of the members’ solo careers.

For example, the original Paul McCartney wrote eleven of the twelve complete tracks on the Beatles’ iconic Sgt. Pepper album, released in May 1967—seven months after Paul’s death. These songs include “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” “With a Little Help from My Friends,” “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” and “A Day in the Life.” In other words, Paul wrote the soundtrack to the Summer of Love but then spent it in the ground.

On George Harrison’s acclaimed triple album All Things Must Pass (1970), the singles “What Is Life” and “My Sweet Lord” originated with Paul.

In his early twenties, Paul wrote what would become John Lennon’s most famous solo single, “Imagine” (1971); Paul penned the lyrics on stationery from The New York Hilton, where the Beatles are known to have been hosted while touring in the mid-1960s. John recorded Paul’s love ballad “Woman” for his album Double Fantasy (1980), released fourteen years after Paul’s death and just three weeks before John’s shocking murder.

Ringo took Paul’s “Octopus’s Garden” as his own; it appears on the Beatles’ Abbey Road album (1969). Paul had probably written the ditty to amuse his little sister. It was a children’s song, like “Yellow Submarine” and “All Together Now.”

Wings, the band formed by Paul’s replacement after the Beatles broke up, released the wildly successful “Mull of Kintyre” in 1977. The song hit number one at Christmastime in the U.K. and was the first single to sell over two million copies nationwide. It had been written eleven years earlier by the original Paul, inspired by his purchase, in 1966, of a farm on the Kintyre Peninsula (on Scotland’s west coast).

“My Love” (1973), “Band on the Run” (1974), “With a Little Luck” (1978), “Coming Up” (1980), and “Ebony and Ivory” (1982) are among numerous chart toppers written by Paul but recorded by his replacement.

“Sir Paul” peddled his predecessor’s songs as recently as 2020, on the album McCartney III. Music videos for Paul’s songs incorporate his original handwritten lyrics.

The foregoing is a very small sampling of the songs stolen from the original Paul McCartney. I want to note here that Paul’s replacement did contribute several songs to the Beatles’ catalog, including one track on the Sgt. Pepper album and at least one track on the White Album (1968).

I have found evidence suggesting that Paul’s songs were, indeed, recorded by others after his death. Raw footage exists of John and George in the studio, working on a song (“Oh My Love”) for what would become John’s Imagine album (1971). The two former Beatles (John on piano, George on guitar), along with John’s coproducers, Phil Spector and Yoko Ono, are trying to figure out which instruments to include on the track. Eight minutes and forty-five seconds into the video, George says, rather shakily: “It sounds to me like one of the ones where he would have had those guitarists playing the rhythm.” In this statement, “he” is Paul, and “those guitarists” are John and George. In other words, Paul would have had John and George provide the song’s rhythm on guitar, rather than have Ringo do it on drums. Presumably, George is speaking in code because multiple cameras are capturing the scene.

[Edit, February 5, 2025: I recently came across some notes I jotted down in 2022 about a video of the recording session for “Oh My Love.” It wasn’t the same video as the one linked above but contained a lot of the same footage. My notes at the time referenced a clue highly suggestive that Paul had written “Oh My Love.” The clue can be found at 5:21 in the video linked above. While John is familiarizing George with the song’s chords, he says, “That’s a Paul song there.” Presumably, John means that a particular chord, chord progression, or sequence of notes was characteristic of Paul’s style.]

Paul’s “Songwriting Fingerprint”

Over time, a convention developed of attributing full or main authorship of a Lennon–McCartney track to the musician who provided lead vocals on it. On Wikipedia, you will find statements like the following (bold and parentheses mine):

- “Here, There and Everywhere” is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1966 album Revolver. A love ballad, it was written by Paul McCartney and credited to Lennon–McCartney. (Because Paul sang lead on “Here, There and Everywhere,” he is presumed to have written it.)

- “Nowhere Man” is a song by the English rock band the Beatles… The song was written by John Lennon and credited to the Lennon–McCartney partnership. (John sang lead on “Nowhere Man,” so it’s assumed that he wrote it.)

- “A Hard Day’s Night” is a song by the English rock band the Beatles. Credited to Lennon–McCartney, it was primarily written by John Lennon, with some minor collaboration from Paul McCartney. (It’s reckoned that John wrote more of “A Hard Day’s Night” than Paul did, because John sang lead on the verses, whereas Paul sang lead on the relatively shorter middle eight.)

Regardless of this “system,” if you examine the Beatles’ songs, whether credited to Lennon–McCartney, Harrison, or Starr, you will find a striking similarity of lyrical form and technique highly suggestive of a single author—whom I contend was the original Paul McCartney.

As a side note, I find it kind of humorous when John Lennon and Paul’s replacement clash over ownership of a song that neither of them wrote (Wikipedia, bold mine):

- “In My Life” is a song by the English rock band the Beatles, released on their 1965 studio album, Rubber Soul. Credited to the Lennon–McCartney songwriting partnership, the song is one of only a few in which there is dispute over the primary author; John Lennon wrote the lyrics, but he and Paul McCartney later disagreed over who wrote the melody.

I doubt this was a tug-of-war over the song but rather two lies, told on separate occasions, that happened to contradict each other.

A hallmark of Paul’s lyrics (exemplified by “Yesterday,” recorded in 1965) is a strong consistency among like parts of a song. For instance, Paul establishes a structure, meter (rhythm), and rhyme scheme for one verse and then applies the same to all the other verses—with a nearly pathological rigor. What this means is that in one of Paul’s songs, you will generally find that each verse has the same number of lines, the same line in each verse contains the same number of syllables, and those syllables are stressed or unstressed according to the same pattern. Paul also adheres to an ordered plan for rhyming from verse to verse.

Paul seems to exert an almost obsessive control over his words, as if he finds comfort in developing “rules” for a song and then writing within those constraints. One might describe Paul’s style as poetic—in an old-fashioned way. (I write sonnets for fun, so I understand this mindset.) Indeed, Paul cited English Literature as one of his favorite subjects in school. Perhaps, as a budding lyricist, Paul took his cue from Shakespeare and other poets he encountered in his studies. Alan Durband, Paul’s English teacher at the Liverpool Institute, gave a filmed interview in 1965 about Paul as an English student and as an aspiring English teacher:

Paul McCartney—a young man who came to me, I suppose, some eight or nine years ago, then quite undistinguished in the musical world but not so undistinguished as a student of English. And it was as an English master that I knew him best… In English, he had a very definite interest, and it wasn’t hard to keep him to his texts…

Playing the guitar was, from probably the age of fifteen, an obsession with him. Indeed, at the age of eighteen, about a week before he left school, he came to me and asked me my advice. He wanted to know whether he should carry on playing the guitar professionally, because he’d been offered a job in Hamburg, playing the guitar at twenty pounds a week, or whether he should carry on and become a teacher, as he’d always intended to be.

Paul’s schoolmaster gave him some sound advice, which the pupil promptly ignored. During the interview, Mr. Durband refers to having been visited by Paul and his father and receiving tickets to Beatles concerts in Liverpool; but his words are intercut with photos of Paul’s replacement. It almost goes without saying that it was the original Paul who maintained a relationship with his trusted instructor from the Inny.

The takeaway here is that Paul’s measured approach to songwriting, especially his heightened awareness of meter, is reflected across the Beatles’ catalog. While appreciating the consistency of Paul’s style, we must leave room for aberration, variation, oversight, experimentation, improvisation in the studio, etc. I will elaborate, with examples and further considerations, at another time, including a discussion of additional traits that characterize Paul’s lyrics (such as the use of internal rhyme, literary allusions, and a strong narrative progression).

I fear I am already losing readers who suffer from metrophobia, “an irrational or disproportionate fear of poetry.” But I promise: this story is about to get really interesting, with hidden messages and even a murder plot.

Couldn’t John Have Written the Beatles’ Songs?

If the vast majority of the Beatles’ original songs were written by one person, as my theory goes, why couldn’t that person have been John Lennon? I can think of a few reasons. First, the “songwriting fingerprint” just described extends to numerous songs recorded after the Beatles broke up. So, if John was the Beatles’ sole songwriter, he would have continued to write songs for his former bandmates, letting them take the credit, as they all pursued solo careers. That scenario seems very unlikely.

Second, John did not display a knowledge of poetic meter. Regarding “Across the Universe,” the third track on the Beatles’ album Let It Be (1970), John stated:

I don’t know where it came from, what meter it’s in, and I’ve sat down and looked at it and said, “Can I write another one with this meter?” It’s so interesting: “Words are flying out like endless rain into a paper cup, they slither while they pass they slip away across the universe.” Such an extraordinary meter and I can never repeat it! It’s not a matter of craftsmanship, it wrote itself.

John sounds mystified by the meter of a song he claims to have written. Yet the meter of “Across the Universe” is not a mystery to someone who has studied poetry a little. The lines of the verses alternate between trochaic (with an extra half foot) and iambic. (In poetry, a trochee is a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed one, as in “flying”; an iamb is an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed one, as in “away.”) In “Across the Universe,” running the lines of the verses together produces a driving, hypnotic quality. I suppose you could write a song as metrically regular as “Across the Universe” without intending to, but it would be awfully lucky; John admits as much in his remarks. I think it’s obvious that John knew “where it came from” (Paul), and that it “wrote itself” because Paul wrote it.

But here’s the most startling part: In the recording of “Across the Universe,” John seems to acknowledge Paul’s passing and perhaps his authorship, by saying Paul’s name, clearly, three times. Specifically, John says “Paul” following each of the first three utterances of “Jai guru deva,” at approximately 0:40, 1:41, and 2:38. John’s third vocalization of “Paul” is so clear and sustained that when I heard it again recently, I got chills. John intones this song so exquisitely I have to wonder if Paul wrote it with him in mind.

But let’s return to when Paul was still bopping around as the Beatles’ bassist.

Why Did Others Get Credit for Paul’s Songs While He Was Alive?

If Paul wrote the Beatles’ songs by himself, why was John’s name in the credits? There are a few possibilities. First, it was John’s band from the start. In 1956, John founded a skiffle group, called the Quarrymen, in Liverpool, England. Paul joined the Quarrymen in 1957; George joined in 1958. By 1960, the Quarrymen had evolved into the Beatles. Four years later, John still saw himself as the one in charge, as evidenced in a filmed interview in Adelaide, Australia, on June 12, 1964. The boys are asked, “Do you have an acknowledged leader of the group?” John says, “No, not really,” as he stands to claim the title. It plays like a joke but reflects the truth of the matter. (In the video, you will see Jimmie Nicol, who sat in on drums for eight concerts while Ringo was ill.)

Because John saw himself as the group’s leader, his ego wouldn’t allow him to be left off the Beatles’ songwriting credits. Paul, at least, got to have his name first on the Beatles’ first album, Please Please Me (1963). On that album’s back cover, the group’s original compositions, including “I Saw Her Standing There” and “Love Me Do,” are credited to “McCartney–Lennon.” On subsequent albums, however, John’s name would be listed first, cementing the sequence that would be commemorated in the myth of the Lennon–McCartney songwriting partnership.

At the time Paul’s name was demoted, George’s name was promoted. Starting with the Beatles’ second album, With the Beatles (1963), George received credit for writing the original tracks on which he sang lead. But he wrote none of them, I’m sorry to say. While Paul was alive, George was assigned authorship of “Don’t Bother Me,” “If I Needed Someone,” “I Want to Tell You,” and “Taxman,” among other songs written by Paul.

Paul clearly acquiesced to the false attribution of his songs; I can almost feel the resentment seething beneath his outward acceptance of this arrangement. But there was a reason beyond the need to satisfy John’s stubborn self-pride that the credits were being spread around: it was theorized that having multiple songwriters within the band would increase the Beatles’ appeal. In fact, moving “McCartney” after “Lennon” might have been part of this campaign—suggesting, subtly, that there was no hierarchy among the Beatles’ equally talented songwriters, who were simply listed in alphabetical order.

So, where did the Beatles’ management get such an idea?

The Think Tank That Probably Had Second Thoughts

The Beatles had started organically; they wanted to make music and entertain people. The members had no idea they were being manipulated by a think tank—which viewed the band as part of a social experiment. This organization intended, presumably, to measure the response of the youth population to the stimulus that was the Beatles. In other words, if the band was packaged in a certain way, what kind of a response would that provoke? Going a step further, could the Beatles be used to control the behavior of the demographic to which they appealed?

You might wonder how this think tank was able to gain access to the Beatles on a level deep enough to mold their style, sound, and presentation to the world. Three men extremely close to the band were also members of the think tank; they very actively exerted influence over John, Paul, George, and Ringo. The intentions of these individuals were relatively benign, I believe, arising from a curiosity about human psychology. But is it ethical to involve people in an experiment without their knowledge?

I don’t think we can know for sure whether the think tank’s interventions contributed to the band’s enormous success. But if you’ve seen early photos of the Beatles, sporting pompadours and clad neck to toe in leather, I think we can at least agree they needed some serious fashion advice. (Pete Best, seen in the linked image, was the Beatles’ drummer from 1960 until August 1962.)

The Beatles’ international popularity had the unfortunate side effect of attracting the attention of truly sinister agents. After that, the three men guiding the band, who were also members of the think tank, had little choice but to comply with a plot to murder and replace Paul McCartney.

Song for an Assassin

The Beatles performed their last concert ever (aside from the famous “rooftop concert,” with Paul’s replacement) at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park, on August 29, 1966. The group returned to England (via Los Angeles), landing at Heathrow Airport on the morning of August 31, 1966. At this point, Paul had less than six weeks to live. During the seventy-two hours prior to the Beatles’ arrival back on British soil, multiple attempts had been made on Paul’s life. Paul was unaware of these attempts, aside from feeling suddenly unwell (due to being poisoned) and noticing bullet holes where he had passed earlier.

Paul was so unaware of the designs on his life that he chatted up one of his would-be assassins and wrote a song for him. Paying homage to the professional killer’s homeland, “Back in the U.S.S.R.” would become the first track on “side one” of the Beatles’ double album known colloquially as the White Album (released two years after Paul’s death). The song refers to getting sick on a plane, which was where the assassin had poisoned him: “On the way, the paper bag was on my knee / Man, I had a dreadful flight.” Indeed, Paul was so ill that when the plane landed, in San Francisco, he parked himself in the lavatory while his future full-time impersonator descended the steps with the rest of the band, mugging for the cameras. (Paul recovered and performed with the band that night.)

I have seen photos, freely available online, that show Paul and the man who replaced him in the same location, at the same time. In these photos, Paul and his double are dressed exactly alike. Clearly, Paul was to be assassinated, and his replacement was to take over on the spot.

I will describe one such photo now but save a full discussion of it for another time. In the photo, Paul and his replacement are pictured on a boat, with some others, in New York City. Paul is the only Beatle visible; he leans against a railing at the left of the photo, conversing with a man who is dressed like a sailor. Meanwhile, Paul’s replacement sits toward the middle of the boat, with a big grin on his face. Perhaps he believes he is moments away from becoming a Beatle; or maybe his smile is a nervous one. Paul and his replacement appear to be wearing the same jacket, shirt, and tie. I don’t know why Paul wasn’t murdered on this occasion—perhaps because someone, unexpectedly, was photographing the scene.

This controversial image, in which people see two (sometimes three) Pauls, has been conflated with photos taken of John Lennon and Paul’s replacement aboard the very same vessel two years later. While the confusion is understandable, the images in question depict two entirely separate events—one that occurred before Paul’s death and the other after.

Why He Had to Go

Beatles fans might recognize today’s date, October 9, as John Lennon’s birthday. In one of life’s weird coincidences, Paul died on John’s birthday. Five years later, when John turned thirty-one, he had a party. During the celebration, John led his guests in a positively dirge-like singalong to “Yesterday” (which Paul had written about an impasse in their relationship). In a recording of this singalong, it sounds like John switches the pronoun in “Yesterday” from feminine to masculine (at 0:45): “Why he had to go, I don’t know.” Then he seems to switch back: “She wouldn’t say.” Was John remembering Paul on that day, lamenting how his bandmate had gone away exactly five years earlier?

The Podcast That Changed Everything

Over the years, whenever the “Paul is dead” (PID) urban legend came up (randomly—I didn’t seek it out), I ascertained that the one and only Paul McCartney seemed to be very much alive. I hardly gave it a second thought (and barely a first).

But in 2018, an episode of The Paranormal Podcast hijacked my imagination in such a way that I had to find out more. The guest expert was addressing “probably the greatest rock-era legend of all.” He began by saying, “For the record, I don’t believe that Paul McCartney is dead.” He went on to describe the “trail of clues” left by the Beatles that Paul had died in 1966, in a car crash, and been replaced with a “body double.” I listened with moderate interest. But when the guest said, “People looked at photographs,” and noticed that Paul was now taller, it was a record-scratch moment for me. I had been walking through my kitchen, in the midst of doing some kind of chore, and I just stopped. I felt like I couldn’t stand. I bent forward at the waist and rested my elbows on the counter, and then my chin on my hands. The show’s host, Jim Harold, sounded similarly staggered: “I don’t know that I’m convinced, but that one blew me away: that there were two different McCartneys based on height alone.”

My curiosity piqued, I devoted myself to studying photographs of the two “Pauls” online. After three long, intense days, I arrived at a conclusion: they were not the same person. I felt destroyed. Wailing, I demanded, “Where is he? What happened to that cute boy?” I had to know. For the record, while I liked the Beatles (I had acquired their compilation album 1962–1966, also known as the Red Album, in college), they were essentially “before my time,” having broken up two years after I was born. So, I was baffled by my profound emotional response to discovering that the original Paul McCartney had disappeared somewhere along the way.

I was closer to the story than I ever could have imagined.

Paul Is Dead

I would catalogue for you the seemingly endless array of clues that “Paul is dead,” but I probably shouldn’t. I went down that rabbit hole six years ago and barely made it out again. Many of the proffered pieces of “evidence” hold validity; others, while highly creative, have little or no significance. I will list a few of my favorites, which you can explore, if you’d like:

- The Sgt. Pepper album cover depicts a funeral for Paul.

- John says Paul’s name three times in “Across the Universe” (discussed earlier in this post).

- George cries out for Paul, over and over, toward the end of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” George’s calls of “Paul!” seem to start at 3:41 but become very clear at 3:54. Hearing his anguish breaks my heart.

- In “All You Need Is Love,” John inserts an homage to the Beatles’ “She Loves You” meant for Paul (at 3:22): “Loved you, yeah, yeah, yeah / We loved you, yeah, yeah, yeah.”

- John’s slowed down but very clear pronouncement “I buried Paul,” in “Strawberry Fields Forever” (at 3:56, and then repeated), is an absolute classic in PID lore.

There are some pretty convincing “Paul is dead” clues that utilize backmasking. I find the sound of music played in reverse a bit unsettling, but if it doesn’t bother you, you might check out the following backward messages: “It was a fake mustache” [“Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise)”], referring to faux whiskers worn by Paul’s replacement; “Turn me on, dead man” (“Revolution 9”); and the particularly disturbing “Paul is bloody” (“Blue Jay Way”).

I have some special words for the PID community: Thank you. Thank you for caring. Thank you for standing up for Paul and his memory. Thank you for having the courage to express your convictions publicly, even if others might question your judgment or even your sanity. Your courage has made mine possible. I feel like I am going very far out on a limb with this post, but I am emboldened by the knowledge that at least a small percentage of the population, as represented by you, has already surmised the truth that Paul was replaced. You were right. You were right.

Proof Positive That Paul Is Dead

We can pore over secret messages in the Beatles’ music and artwork, but the most compelling evidence that Paul McCartney died and was replaced is entirely circumstantial: he didn’t attend his father’s funeral.

Let me try to impress upon you how unlikely this scenario would have been, had Paul been alive when his father passed. By all appearances, Paul was very close with his father. For example, he took an active interest in Jim McCartney’s romantic life after the gutting death of the family’s matriarch, Mary. When Jim became interested in a vivacious young widow, Angela Williams, Paul had known a proposal was imminent; he phoned the evening Jim was planning to pop the question (5:10). When Paul learned the answer was yes, he drove straightaway from London, a trip of about four hours, to see Angie and her four-year-old daughter, Ruth. (In the linked video, Ruth says something interesting, starting at 6:42. Referring to Paul, she remarks, “We were eighteen years apart”; her use of the past tense would seem to suggest her brother is no longer alive.)

Paul had recently purchased a lovely house for his father in Heswall, a coastal town about ten miles from Liverpool. He had also arranged for his father not to have to work as a cotton salesman anymore, or ever again. Paul gave his father quite an unusual gift for his sixty-second birthday: a racehorse! It was reportedly well-received. I’m sure Paul felt grateful to be able to make his father’s life a little more comfortable and enjoyable.

Do these seem like the actions of a man who would skip his father’s funeral for any reason other than having beaten him to the grave?

Paul’s replacement was in Europe, touring with Wings, when Jim was buried. Mike McCartney had to lie to explain his brother’s absence: “It was no coincidence that Paul was on the Continent at the time. Paul would never face that sort of thing.” This comment is incredibly painful, but I don’t blame Mike; I’m not sure what else he could have said.

You Are Getting Sleepy

Why would Jim McCartney abide the replacement of his son, whom he loved, with a stranger? Why would Mike McCartney make his brother’s replacement the best man at his wedding? Why would John, George, and Ringo accept a new band member and move forward as if nothing had changed, aside from their clothes and amount of facial hair? Why would the Beatles’ manager and the Beatles’ producer continue to manage the band and produce their music with an imposter in Paul’s place?

From what I know of the situation, and of the players involved, the answer is a combination of coercion and hypnosis. I don’t know to what degree, if any, these forces are still in effect. Presumably, however, real relationships developed, over time, between Paul’s replacement and the people who had been close to Paul.

How to Tell Paul and His Replacement Apart

I don’t encourage anyone to spend a lot of time trying to distinguish between Paul and the man who replaced him, as this exercise can prove frustrating, but here’s a quick guide to a few of the ways in which the two men differed. If you choose to do some exploring of your own, just keep in mind that photos can be misleading or even doctored.

Stature. At the end of 1966, “Paul McCartney” was suddenly several inches taller than John Lennon and George Harrison. Until then, the three had appeared to be about the same height, as supported by their self-reports:

- John: “just under six feet tall”

- Paul: “just above 5 feet 11 inches tall”

- George: “five feet ten inches tall”

(Knowing John, he was probably exaggerating a bit when he said he was almost six feet tall.)

John and George had shared a mic with Paul onstage countless times, even all three together—as when the Beatles performed “This Boy” at the Washington Coliseum, on February 11, 1964, during their first concert in America. You can really see (starting at the 6:37 mark) how close in height they were—and how cute! They probably couldn’t believe they were in the United States, in the nation’s capital, playing for such a large and receptive audience. Using the same staging, Paul’s replacement would have seemed to tower over John and George. A direct comparison is impossible, as the Beatles didn’t tour again after Paul died.

I hesitate to direct you to images showing the taller, broader man who replaced the original Paul McCartney, as arguments might be made about camera angle, distance of the subject from the camera, posture, heel height, etc. And such arguments might be valid! But I believe this small selection of photos, considered together, is suggestive:

- Sgt. Pepper album cover, front and back (scroll down to see both)

- Outtake from the photo shoot for the Sgt. Pepper album cover (scroll down)

- Magical Mystery Tour photo

- Undated black-and-white photo

Hair. Paul’s hair parts naturally on the left, as seen in his purported passport photo; his replacement’s hair parts naturally on the right, as seen in a seeming recreation of the same (hand-dated nineteen days after Paul’s death). Of course, hair can be styled against a natural part or even trained to take a new part.

I believe that Paul, toward the end, was made to wear a hairpiece at times, to conceal the way his hair fell; that way, after he was replaced, his part wouldn’t seem to have suddenly relocated. For example, as Paul boarded a plane from Los Angeles to San Francisco, on August 29, 1966, he appeared to be wearing a lopsided hairpiece toward the front of his head; his part was not visible. We have already seen Paul’s replacement as he exited the same plane, with John, George, and Ringo. (Paul was sick in the lavatory, if you’ll recall.) The replacement’s hair was styled like Paul’s, without an obvious part.

Paul was caught possibly checking the position or stability of his hairpiece two days later, after the band touched down in London. In newsreel footage, we see Paul put his right hand on top of his head (at 0:37); he then scratches his head, possibly to distract from his true intention (to make sure his hairpiece is where it should be). He concludes this shifty maneuver with an awkward pivot. In the closeup interview that follows (at 0:50), Paul’s part seems to be very well-hidden behind a thick fringe.

Eye color. Paul described himself as having “very dark (almost brown) hazel eyes.” Paul’s replacement also appeared to have hazel eyes, but they tended toward green (starting at 0:49). According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology: “Hazel eyes are a mixture of pigment color and color from scattered light, so they can look different in different lighting conditions.” Fortunately, we have Paul’s description of his own eyes, with which he was presumably quite familiar under various lighting conditions.

Face shape. Paul’s face is rounder; his replacement’s face is longer.

Vocals. To my ear, Paul’s singing voice is smokier, raspier, as on “Eleanor Rigby”; his replacement’s singing voice is slipperier, smoother, as on “Penny Lane.” Regarding these two songs: “Eleanor Rigby” (released August 5, 1966) was the last Beatles single on which Paul sang lead; “Penny Lane” (released February 13, 1967, in the U.S.) was the first Beatles single on which his replacement sang lead. Paul had written most of “Penny Lane,” but his replacement finished it. For “Eleanor Rigby,” Paul won a posthumous Grammy for Best Contemporary (R&R) Vocal Performance, Male or Female. At the same ceremony, John and Paul received the Grammy for Song of the Year, for “Michelle,” which Paul had written for his daughter in France.

Don’t Hate

Before you get too mad at the American studio musician who assumed Paul McCartney’s identity so convincingly, he had little choice in the matter—though he certainly capitalized on the gig in some less than honorable ways and failed to meet some very serious responsibilities (beyond missing his doppelgänger’s father’s funeral).

Becoming an instant megastar the likes of Paul McCartney would obviously have its perks. But I want to share just a few of the pitfalls of impersonating the Beatles’ dead bassist: Having to relearn how to play the guitar and write, because you’re right-handed whereas he was a lefty; having to study and emulate your predecessor’s idiosyncratic gestures and speech patterns; having to fake a British accent for the rest of your life; having to pretend strangers are your family members; having to describe the inspirations behind dozens of songs you didn’t write; and having to come up with fake memories of Beatlemania for an exhibition of the other guy’s photos at the National Gallery in London. Plus, when people say you look great for eighty, you can’t tell them you’re actually eighty-five!

When you think about it, Paul and his replacement share a truly unique bond: they both walked the earth as Paul McCartney of the Beatles.

Paul Is Alive (Sort Of)

[Edit, October 15, 2024: Someone I know asked me to consider deleting this section from my post, as it might damage my credibility as a reasonable, rational human being. This person typically speaks their mind and lets the chips fall where they may. I almost never do that. I am quiet and modest. I am not provocative. But out of respect for their concern, I am issuing the following clarification: I am a writer. I am able to distill both flights of fancy and truths into words. Therefore, what is written here might be fiction. Or it might represent reality. Either way, it’s my story. I am reminded that Mary Shelley first published Frankenstein anonymously because she feared her children might be taken away from her—as a woman capable of penning a tale of horror. Her full name appeared in the second edition, five years later. Do we wish Mary Shelley had censored herself, choosing subject matter deemed appropriate for a female writer of her day? Are we not glad she ultimately took credit for a book that went on to inspire generations of women authors and continues to captivate readers more than two hundred years after its release?]

So far, I’ve been talking about Paul in the third person. I don’t expect anyone to believe this, and sometimes I don’t believe it myself, but I was Paul McCartney. It probably took longer for me to accept this than it should have—not because I didn’t believe in reincarnation but because then I would have to own Paul’s pain. I was feeling it anyway, but if I accepted that I used to be Paul, I’d have the added burden of self-pity. The first few years were the roughest. I think I’ve processed much of the grief—not in any organized way, because you can’t see a traditional therapist about a past life, but through tears, lots of tears.

I know I sound like those people who discover, through hypnosis or a psychic reading, that they were once Cleopatra or Napoleon. (My greatest regret is that I wasn’t Chaucer.) But whether or not I used to be Paul McCartney doesn’t affect the fact that he was replaced by a lookalike. If you simply can’t believe in reincarnation, I get it. On the other hand, just because something seems implausible to you, or doesn’t fit into your view of the world, doesn’t mean it isn’t happening.

I get sad speculating that if people find out Paul McCartney died almost sixty years ago, they will look back and think, “Huh. We didn’t really miss him.” Debunkers of the “Paul is dead” urban legend already say things like: “If they did replace Paul McCartney with a double, they managed to find, somehow, a left-handed bass player who was perhaps even more talented than the original Paul.” I hope you can understand how painful it is to hear such a dismissive remark (though I know the speaker had no idea the real Paul was listening).

It’s hard to convey the desolation accompanying the realization that you died, and virtually no one noticed. And those who did notice—those closest to you—carried on with a complete stranger in your place! Having been betrayed so thoroughly by everyone in your life, you can only turn it around on yourself: you must not have been deserving of their loyalty. You can cry, and you do; but you cry into a void. You are perfectly alone in your knowledge. Your story is too extraordinary to share. Who would believe it? Who would entertain even the basic premises—that Paul McCartney died in 1966, was replaced by a lookalike, was plagiarized more egregiously than perhaps any other musician in history, and is now a writer in California (well, first a baby, and later a writer)?

Regarding this last premise, I could tell you that I started piano lessons when I was five, quitting promptly when I was six and leaving my parents with an expensive, useless piece of furniture. I could tell you that, as I child, I made milk-carton guitars strung with rubber bands. I could tell you that, as a preteen, I regularly sang into a hairbrush in the bathroom mirror. I could tell you that, as a young adult, I cried at the end of a documentary about the Beatles—which didn’t make any sense, because the documentary ended with the band’s attainment of success and popularity. I could tell you that I found myself fascinated with Paul McCartney’s profile, when I saw a caricature of it once, probably on the cover of Revolver (1966). I could tell you that in recent years, I returned to the piano, learned how to play a real guitar, and wrote some songs. But these aspects of my personal history, even taken together, don’t prove that I used to be Paul McCartney.

I have, however, encountered one person who seemed to recognize me. (I will speak vaguely, to protect his privacy.) This person didn’t come out and say, “I remember you from when you were Paul McCartney.” But he suggested, via seemingly out-of-the-blue comments, that he was looking through me to the cute, left-handed bass player within. I saw this individual in a professional context, typically several times a year. Following is a summary of his increasingly specific remarks, which included references to the Beatles and to celebrities whose last names begin with “Mc”—culminating in “McCartney.”

- September 2018: First visit. No indication of recognition.

- October 2018: Second visit. The person brought up having attended a local performance eight years earlier featuring music by the Beatles and a guest appearance by the Beatles’ producer, George Martin. He asked, “You know who George Martin is?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “Really?”

- May 2021: As the 1970s hit “I Go Crazy,” by Paul Davis, played over the sound system, the person remarked: “Can you imagine what it would be like to have someone love you so much they go crazy when they look in your eyes?” (I was a bit offended that he assumed I would have no familiarity with such a situation.) Then he said, “Can you imagine what it would be like if everyone who looked at you went crazy?” Then he said, “Like if you were one of the Beatles?”

- October 2021: The person shared a “dream” from that morning, in which he’d had to perform a service for a martial arts celebrity with a last name starting with “Mc,” who was due to go onstage. Later, he quoted Ringo Starr (“I’ve got blisters on my fingers!”) and brought up another celebrity whose name begins with “Mc” (Ewan McGregor).

- November 2021: The person mentioned the movie Spy, starring Melissa McCarthy, but he said her name wrong, as Melissa McCartney. I repeated her name, but correctly. About a minute later, he recapped the movie’s cast and got the name wrong again, saying “Melissa McCartney.”

Regarding the math, I was born seventeen months and twenty-two days after Paul died. Interestingly, as Paul, I was born within five months of my mother in this life.

Learn to Fly

When Paul died, he left behind the song “Blackbird.” His replacement recorded a very lovely version of it for the Beatles’ White Album. While I was researching the “Paul is dead” urban legend, I came across a video of Paul’s replacement learning how to play “Blackbird” in the studio. The footage is quite grainy, and for a few moments, I let myself hope I was watching the original Paul—possibly working out the melody for a new song, on a break from recording something else (maybe Revolver, his final album with the Beatles). But studying the figure in the video left me with the sad truth: Paul was gone.

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, which I quoted at the beginning of this post, takes its title from a poem by Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872–1906), considered “one of the first influential Black poets in American literature.” Dunbar writes of a bird in a cage, whose “wing is bruised” (from beating it against the bars) and who “would be free.” At the end of the poem, we learn why the caged bird sings: as a prayer, as a plea to Heaven. The poem, called “Sympathy,” is so beautiful that I wish everyone the experience of reading it. It’s inspiration, perfectly realized. It’s the reason poetry exists as a form of expression.

I wonder if Paul encountered “Sympathy,” by chance, as I have done; was similarly astounded; and reached for the nearest pen and scrap of paper. Might Paul have written “Blackbird” to explore what happens after Dunbar’s bird is liberated, perhaps through divine intervention? What does a wounded bird, who has known life only in a cage, do with his newfound freedom? What does he have the strength to do? The more I think about it, the more I can envision a dusty volume containing Dunbar’s poem still sitting on a shelf in Paul’s London home, which remains among his replacement’s assets, as far as I know.

Paul didn’t get a chance to share his version of “Blackbird,” so I offered him my hands and vocal cords. He said, “Well, these will just have to do now, won’t they?” After watching the video (below), you might find yourself wondering: “Isn’t it hard for a novice player to sing along while fingerpicking a guitar?” But rest assured: I only make it look difficult.

What Happens Now?

Just a few dozen people follow my blog (thank you!), including bots, so I don’t expect my life to change once I hit “Publish.” Since 2021, I have been writing, recording, and posting very pointed songs about Paul’s experience—with nary a ripple. These include songs for Paul’s brother, sister, hometown, fiancée, three children, bandmates—and even his replacement.

Paul and I will be back here toward the end of next week with another new video, also recorded live on my living room couch. It’s for a song Paul left incomplete when he died but has since finished (with a little help from his friend, me).

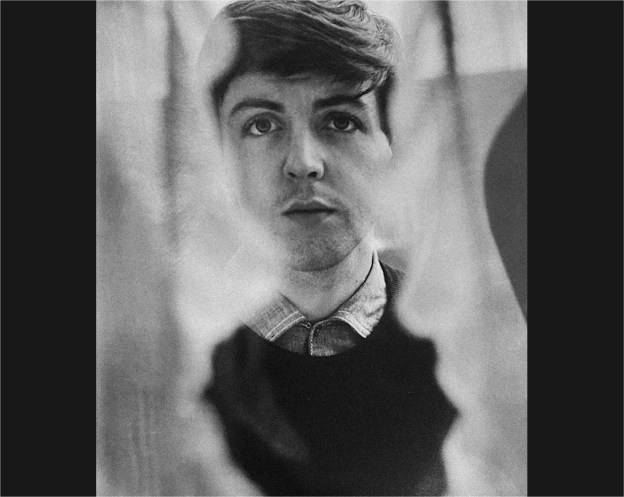

CREDITS: The photo at the top of this post was taken by Mike McCartney, in 1962, at 20 Forthlin Road, Liverpool; I borrowed the image without asking, but I’m thinking Mike will give me a pass since I’m his brother (or at least harboring his brother in my subconscious). All links in this post were active at the time of its publishing, on October 9, 2024.

Pingback: Is This Town Big Enough for Two Paul McCartneys? | Novel-Gazing